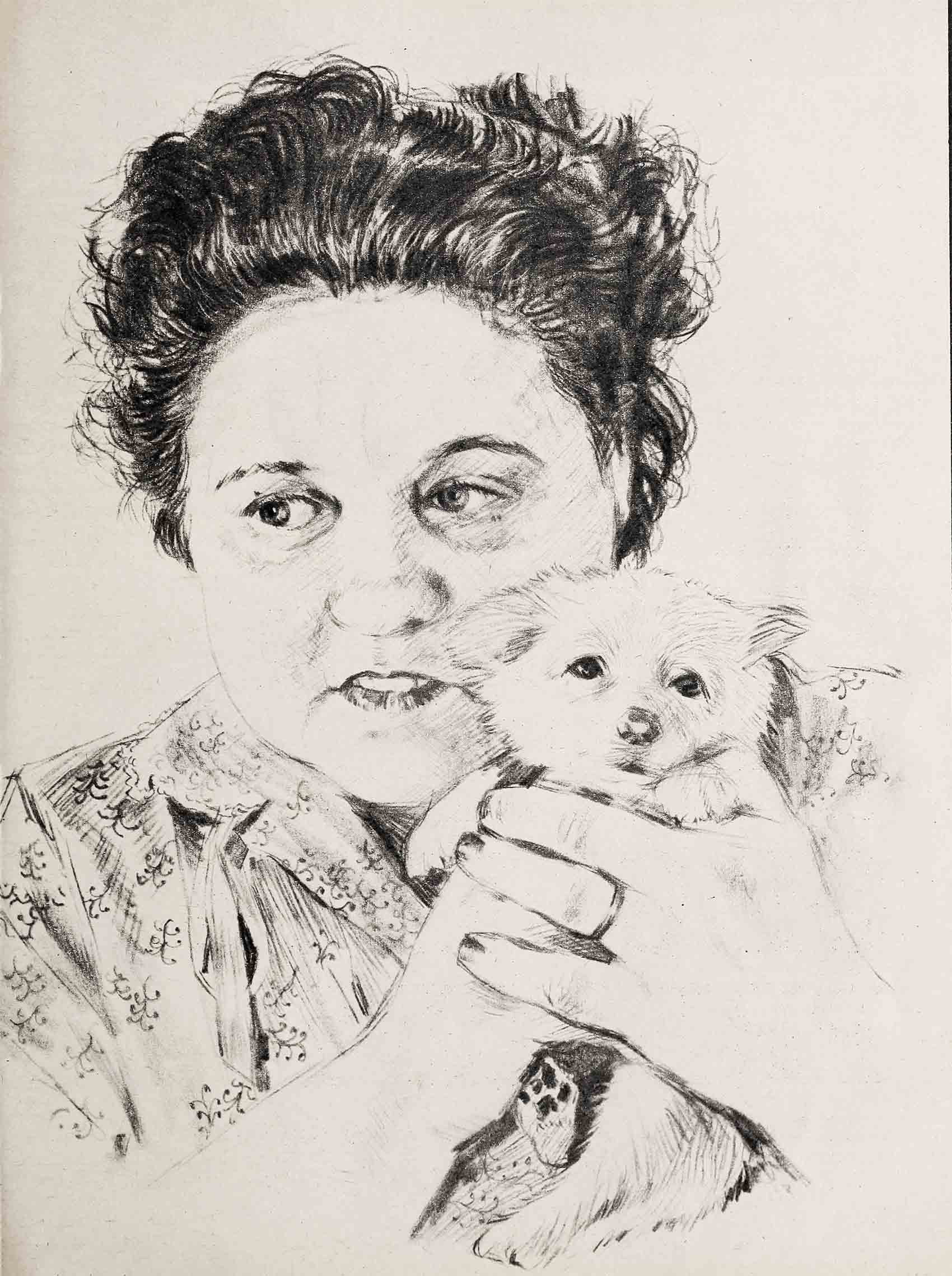

The Life And Death Of Gladys Presley

GLADYS SMITH PRESLEY looked at the cabin from down the road and she smiled. Usually, even though she was only nineteen years old and not at all unhealthy, she was so tired after her two-and-a-half mile walk from town and the dress factory there where she worked, that she could barely manage to catch her breath and talk right for a while, let alone smile. But tonight she smiled. For she knew that this was the night Vernon, her husband of a year, was putting the finishing touches on the little cabin he had just built for them, built with his own bare hands and sweat. And she knew, too, that this was the night she would tell Vernon what she had found out at the doctor’s office during her lunch hour that day.

She smiled to herself again and looked up at the roof.

“Vern’,” she called out from the road, a few minutes later, “look down from that ladder and listen to what I’ve got to tell you.”

But all of Vernon’s concentration was on getting this house of theirs done.

“What’s that?” asked Vernon Presley, busy with a hammer and not looking.

“Just that I think it was a good idea that you’ve worked hard like you have and that you built us a two-room house instead of a one-er like most of the others ’round here,” said Gladys.

“Sure thing,” said Vernon Presley, half to himself, still not looking.

“After all,” continued Gladys, “when there’s a tiny baby howling and scampering around, it don’t hurt none to—”

She stopped in the middle of the sentence and roared with laughter as she watched Vernon drop the hammer first, then turn around and look down at her, then come shooting down the ladder, and then come running over to her and grabbing her plump young arms in his strong hands.

“You say baby?” Vernon Presley asked.

“I did,” Gladys answered.

“You sure?” he asked.

“I was only told so this afternoon by the finest doctor in all East Tupelo, Mississippi,” Gladys answered.

Vernon let out with a wild, hollering whoop. And then he kissed his wife.

“And,” Gladys went on, “this doctor, he asked me a lot of questions about our family history and after I was through he said, ‘I wouldn’t be surprised if it was twins, Mrs. Presley.’ ”

“Say that again, ma’am,” Vernon asked, his face paling from sun-red to sandy white.

“You heard me,” Gladys said, laughing again, tickled by her husband’s first show of daddy-nerves.

Vernon turned and looked back at the house he’d just finished building. “Maybe I should have made it three rooms,” he, said.

More important than money

“We couldn’t afford that, Vern’,” Gladys said. Suddenly, the laugh she’d been laughing vanished and she was serious now. “We couldn’t afford that. We can hardly afford what we got . . . But there is one thing we canafford if it’s twins, poor as we are. That’s love, Vern’. That’s one thing we don’t have to save for and buy. That’s one place where this poorness of ours don’t count.”

She took her husband’s hand in hers, this pretty nineteen-year-old girl turning woman, and she squeezed it hard.

“I hope it is twins,” she went on to say. “I hope and wish it with all my heart so’s we can double up on that one thing we know we can give ’em—love, and so we can love ’em and love ’em and love ’em, and so when they’re big they can always say, ‘That ma and pa of ours, they didn’t have much of nothing, but they sure were rich in love. . . .”

Gladys Presley learned a few months later that her wish would come true. And then a few months after that, on the night of January 8, 1935, she gave birth to two sons. One of then she named Aaron. The other she named Elvis. The baby named Aaron died a few months after he was born. The other baby, now Elvis Aaron, was—though unusually quiet for a new-born—both powerful and healthy-looking and it was clear that he would live. It was clear, too, from the expression on Gladys Presley’s face as she held him in her arms that first time and watched his closed eyes squint and waited for him to unloose his lips and cry, the way her other baby had cried at first and would never cry again, it was clear from all this that tiny Elvis Aaron would get his full share of the doubled-up love his mother had talked about that happy night so many months before out on the dust-covered road. . . .

The next years were not easy ones for Gladys Presley. Vernon, a house painter, a good one, had trouble finding work because most people in Tupelo and East Tupelo and thereabouts didn’t have enough money at that time to worry about peeling walls. So the money situation was always tough. And so, not long after Elvis was born, Gladys decided it would be a good idea for her to go back to work at the dress factory.

“I’ve got to,” she told people who told her she was silly, that she was still too weak from giving birth. “We got a boy to bring up and he’s going to be brought up right. He’s going to have shoes so’s he can go to school and church, and he’s going to have books so’s he can read and toys so’s he can play and be happy like other kids.”

At first, Gladys Presley managed it well enough.

She’d never give up

But after a few years, her health began to fail.

The walk to town every morning, the walk back at night, the hours over the sewing machine, the Hours over the stove, the worrying about Vernon when he found it harder and harder to get work, the worrying about Elvis when he came down with a case of this or that, like he was always doing—there were other women who might have been able to manage it, but it was turning out to be hard on Gladys Presley, too hard.

She wouldn’t give up, though, not for all the begging anybody, her husband and her son especially, could muster.

“Will you stay home tomorrow and get some rest?” her husband would ask on a night when Gladys would be working at something around the house and sneezing at the same time, her eyes glazed with fever and her face flushed.

And Gladys Presley would answer, “I passed that new grocery store in town today, Vern’, and they got a sign advertising milk three cents cheaper than I been paying. I got to try ’em. If it’s really good milk it’ll be quite a saving.”

“Ma,” her son would ask on a night when Gladys Presley would stop suddenly in the middle of whatever she was doing and look as if she were about to faint, as she would reach for a chair or a wall to lean against to keep from falling, “can’t you let things be and take it easy and stop working so hard, Ma?”

And Gladys Presley would say, “Elvis . . . you know . . . I was reading in the papers tonight that a wonderful group of Gospel singers is going to be at the church Sunday night. And we can go. And you can sing along with them, like you like to. And . . . and ain’t that going to be wonderful, Son?”

This is the way it went for years.

But then, finally, came the night in 1949 when her husband and her son, fourteen years old now, decided that they should move away from Mississippi and take Gladys Presley to an easier life.

The father and son talked it over first. Then they talked to the woman of the house. They told her to set, that they had something important to say.

“We been hearing,” Vernon began, “that things are pretty good up Memphis-way for jobs and better money. We been thinking we should all go live up there for a while and try it out.”

“It’s a big city, Ma,” Elvis butted in, “where they got lots o’ houses, which means Pa can do a lot more painting.”

“Good idea?” Vernon asked. “Do you want to do it. Do you want to move?”

Gladys Presley didn’t answer for a while.

Then she shrugged and she said, “As long as they got churches and schools in Memphis, as long as you and Elvis will be happy, then it’s all right with me.”

For the next few moments she looked around the little house she had known so well for the past fourteen years, thinking her private thoughts.

Then she got up from the table and went to start the supper dishes, and to pray silently that what they were going to do was the right thing to do. . . .

A new home and a bad break

Memphis seemed fine at first to Gladys Presley. Vernon was finding work. Elvis was going to a good school. And even though the house they’d moved into on Alabama Street was only a one-roomer, smaller even than the house back in Mississippi, it was nice and it was clean and there was something about the way the big Tennessee sun shone through its windows all day that seemed to promise warm, happy things to come.

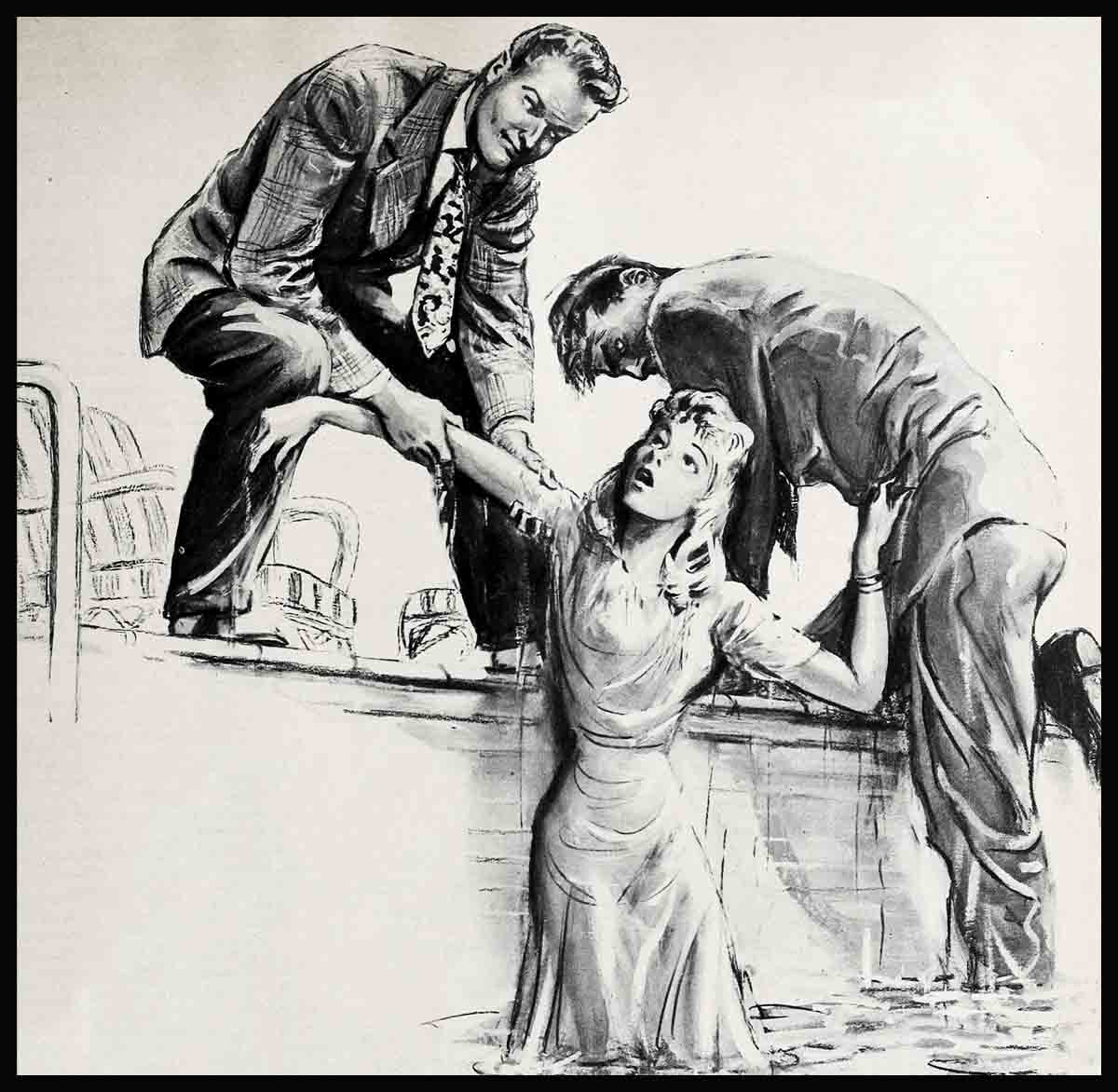

But then it happened, the bad thing, the worst thing that could have happened. One day while working, Vernon Presley fell from a ladder and broke his back. He was taken to the hospital. And to pay his bills, Gladys Presley got a job at the same hospital and for more than two years she bathed people, changed beds, carried bed-pans and worked harder than she’d ever worked before.

To help, her son Elvis began to work too, after school; as a movie usher, then as a factory hand, then as a truck driver.

Gladys Presley hadn’t wanted him to work. She’d wanted him to go to school and study during the day and to do at night what the other kids in Memphis did—get together and talk and laugh and play and sing.

But this wasn’t the way it was to be, it seemed.

And came the night when Elvis, nearly seventeen now, came home from work at eleven o’clock and was so exhausted he fell asleep right in the middle of his supper of mashed potatoes and hard bread, asleep, right there at the table in his chair across from her, and Gladys Presley—who’d never once complained about anything in her whole life—slammed her fist hard into her lap now and cried out, “Oh Lord, Lord, ain’t this family of ours ever going to have any luck?”

She had no way of knowing that one day, in about two years’ time, her son, Elvis, would buy a guitar and make a phonograph record of his singing and that the Lord would thus answer her cry. . . .

Those few years after the first record was made—and there were to be only a few more years for Gladys Presley—saw all the wonders of the world thrown suddenly into her lap. Suddenly, overnight, her son was one of the most famous people in the world. Suddenly, her son was one of the richest young people in the world. Suddenly, her son was moving her and her husband from their one-roomer on Alabama Street to a $40,000 house on Audubon and then to a $100,000 mansion called Graceland, just outside Memphis—a mansion with servants, red carpets, a swimming pool, white-and-gold-finished pianos, a gigantic refrigerator always stuffed with food—with everything in the world.

Gladys Presley was happy now. Yes, she was unused to this way of living and she became shy of people who made such a fuss everytime they saw her and she stayed more and more inside the stone walls of Graceland as time passed. And yes, she would get upset when she picked up a newspaper and read some of the terrible things some people were writing about her son—about how he was leading other young people to sin through his songs—and she would sit with her husband at night and say, “Don’t they realize that Elvis’ songs have never hurt a body, young or old, and that he’s got joy inside him and that he’s just passing on that joy when he sings?”

Yes, there were the times when Gladys Presley’s heart was sad and confused.

But, overall, she was happy. For through all this period, she and her husband had their son’s love, stronger than it had ever been.

And in this period came the one moment of supreme happiness, the pure moment of pride in her offspring, the moment she would never forget for as many days as she had left to live on this earth.

The moment occurred at Graceland, one morning. Gladys sat in the downstairs drawing room, sewing. In the next room two colored women servants—one young, one very old—were working and a little boy was playing. The boy was a grandson of the old servant, a boy of four or five who would come up to Graceland occasionally to visit with his grandma. He was a great little talker. And though the door was almost closed, Gladys Presley could hear him talking away about everything under the sun.

As good as Mr. Presley

At one point, when he began rambling on about how tall he was going to be when he got older, Gladys heard one of the servants, the younger one, ask, “Say, tell me now, just what are you going to be when you grow up and get so big?”

“I’m gonna be famous and good,” she heard the little boy answer.

“Like a president of the United States or something?” she heard the young woman ask.

“No,” the little boy answered, “like Elvis Presley.”

Gladys began to smile. She’d just started to smile, in fact, when she heard the older woman, the boy’s grandmother, say, “Amen to that, my little baby. Amen to that. And never mind about the ‘famous part. Just be as good a person as Mr. Presley is, as good as he is to his parents and to all of us who work here and to all his friends he keeps in clothes and food. Just be like that, my little baby, good, and I’ll forever say, ‘Amen, Amen.’ ”

Gladys Presley sat in her chair, her sewing in her lap, long after the two servants and the boy had left the adjacent room.

If she’d been the kind of person who cried easily, she would have wept for joy now.

In the last couple of years she’d heard all kinds of people say all sorts of fine things about her son—Governors, Hollywood producers, record company presidents, press agents, important people from important walks of life.

These things she’d heard had always consoled the hurt she’d felt when she’d read some of the bad things.

These things had made her feel better than she might otherwise have felt, even though deep down she knew that some of these people had said what they’d said because they were expected to or because it would benefit them or because of other mysterious reasons she couldn’t quite understand, but felt.

But now, as she remembered those warm Amens that had come from the depths of the heart of a cleaning lady, old and simple and wise—now, as Gladys Presley sat there in her mansion, the simple word Amenechoing and re-echoing through her mind, now for the first time . . . and maybe for the only time . . . did she feel that these new possessions and this new life and all this success that had been showered on her son was truly worthwhile. . . .

The beginning of the end—

It was during the summer of 1957 that Gladys Presley got sick again. People who should know say that she suffered from a nervous condition. Says one, “She wasn’t too well to begin with and the tensions were becoming too great and, though she fought it happening, it happened and her nerves snapped wide apart.” Says another, “The constant clamor of fans had begun to bother her, crank letters to worry her, and the repeated reflections on her boy’s movements and morals to hurt her. . . . Even little things had begun to get on her nerves. One day, one of Elvis’ buddies came in from the swimming pool and let out a piercing yell just as he got into the house. The sudden shriek so startled Mrs. Presley that she went into a nervous collapse. The Presleys then had no family doctor. He was a luxury they had not been able to afford during their long, lean years and had not needed since, until now. Vernon Presley telephoned the Doctors’ Exchange and asked that a physician be sent to Graceland. When the doctor came, he gave Mrs. Presley a sedative and began treating her for a nervous condition, a condition that we know now so weakened her that when her liver became infected with hepatitis her heart began to grow weak, too . . . weaker and weaker and weaker. . . .”

The hepatitis attack occurred on Saturday, August 9, 1958. Gladys Presley was a few months past her forty-second birthday. She and her husband had just returned from visiting their son, now a soldier, at Fort Hood in Sabine, Texas. They were, in fact, still on the train, pulling into Memphis station, when Gladys felt the first attack and brought her hands to her stomach and told her husband that she hurt, hurt bad.

Vernon took her straight to their doctor’s office, where she was examined and en ordered straight into Methodist Hospital.

At about five o’clock that afternoon, Gladys Presley picked up the phone by her bed and phoned Fort Hood.

“I don’t feel so good, Elvis,’ she said into the receiver, a few minutes later. “I know I shouldn’t worry you or bother you. But I just wanted to talk to you a little bit.”

“No, no,” she said, “I don’t want you coming up here.” She tried to smile. “I don’t want you getting in trouble with none of those sergeants,” she said. . . .

The final courage

Elvis flew up from Texas four days later. He’d been in constant touch with his pa and the doctor ever since he’d heard from his mother. At first, they’d told him what they believed to be the truth, that Gladys Presley was sick but that her condition was not too serious.

And then, as the days passed, her condition. worsened. And, finally, Elvis was told to apply for an emergency leave, that his ma was asking for him and that it might help her if he surprised her with a visit.

Gladys Presley seemed fine that Wednesday afternoon at two o’clock when her boy came rushing into her room. She’d just finished lunch and she was sitting up in bed and she threw out her arms and she said, “My son, my son, I’ve wanted so much to see you.”

For a while, she talked and laughed with her boy. And then a while later her doctor came into the room to examine her and she joked with them both.

The doctor smiled and asked Elvis to please leave for a few minutes since he would like to get on with his examination.

It was about half an hour later when the doctor walked out of Gladys Presley’s room and over to Elvis.

“Ma’s all right, Doctor, isn’t she?” Elvis asked. “She’s getting better, isn’t she?”

The doctor didn’t answer exactly. Instead he said, “Why don’t you go in for another while? And then you can go home and get some rest and let your ma get some rest, too. She hasn’t got as much strength as it seems.”

Elvis stayed till about six o’clock that night. And then he did go home, after kissing his mother and promising that he’d be by first thing in the morning.

As he left, he wondered why his pa—who’d since come by—didn’t come along with him now, too; why his pa had whispered something to him about staying in the room all that night and sleeping on a cot next to Ma’s bed. This seemed kind of funny to Elvis as he left, kind of strange. But he didn’t ask any questions now. Everything seemed. all right, in a way; but something was wrong, too—this Elvis knew. And maybe, he figured, maybe if he didn’t ask any questions, what was wrong would disappear and tomorrow would come and Ma would prop herself up in bed again and they would talk some more and laugh some more and everything would be all right.

At three o’clock the next morning, the phone alongside Elvis’ bed rang. He opened his eyes and for a few long moments just lay there and let the phone keep ringing. He knew what had happened. He knew his ma had died.

When, finally, he did pick up the phone and heard his father’s voice tell him how it had happened—a heart attack from out of nowhere. So quickly, the sudden heavy breathing, then the no-breathing—he began to weep. He hung up the phone. He put on his shoes and pulled on a pair of pants and went to a drawer and pulled out the first shirt his fingers got hold of, a white stage-shirt with lots of frilly lace running up and down the front. And, still weeping, he left for the hospital.

His father was waiting for him outside his ma’s room. Neither of them spoke.

When Elvis looked out at the still figure on the bed he called out, “There was gonna be so much to come, Ma, so much!”

Then he rushed over to the bed and brought his dead mother’s hand to his lips and kissed it, over and over again.

And then again, he began to weep, loudly, like a child.

And it wasn’t until much later, when the crying had stopped and the tears were hardened in long lines on his face, that he looked down at his mother’s face and noticed for the first time that she had died smiling.

He didn’t know why she had smiled during that last moment of life.

Nobody does, or ever will.

But maybe in that last moment of her relatively short life Gladys Presley had thought of a lot of things, of her good husband and her good son and all the wonderful things that had come to him.

And maybe she’d thought, too, about that happiest moment in her life and an old Negro cleaning woman.

And maybe the old woman’s voice had come back to Gladys Presley in that last moment and, with it, the voices of a chorus of watching angels as together they all shouted a tremendous and joyous and final Amen.

THE END

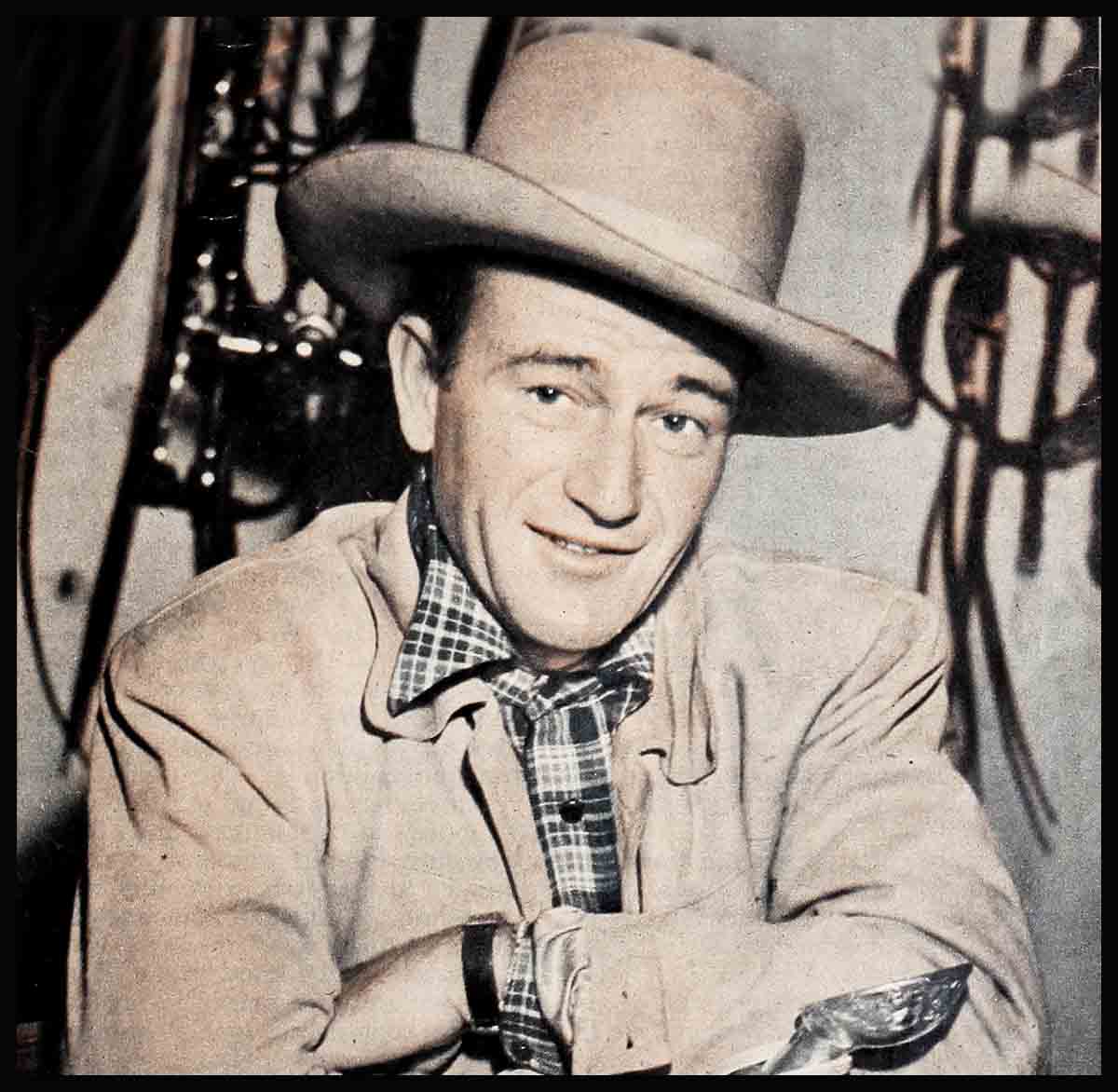

Elvis’ last picture was KING CREOLE for Paramount.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1958

No Comments